Hardly a day goes by without at least some coverage of the effects of the staff shortage. Baby boomers – marked by high birth rates in many European countries – are exiting the job market and, often, cannot be replaced to the same extent by a younger workforce. How strongly and in which areas is the wine industry impacted by this staff shortage, and how does it react to it? What workforce-related opportunities and risks does the industry see in the near future? The ProWein Business Report 2022 was already heavily focused on his central issue.

1. The Labor Shortage: The Central Issue

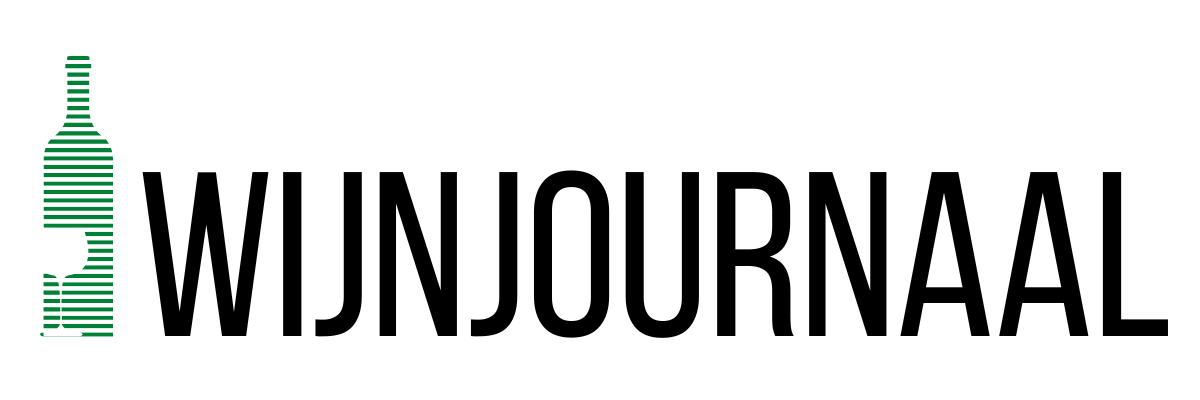

Overall, almost every other company (45%) in the wine industry reports having been affected by staff shortages over the last two years (2021 and 2022). When it comes to wine producers, staff shortages are slightly above the industry average – half of all companies are affected – with larger wineries generally suffering a bit more (Figure 1, left). The main reason for the greater staff shortages in production is the strong seasonality of the work involved – including during the harvest and vegetation periods.

Figure 1: Frequency of staff shortages for wineries (left) and the wine trade (right)

On the trade side, hotels (90%) and gastronomy (66%) are hit hardest by staff shortages. During the pandemic, these sectors were forced to close for extended periods due to lockdowns and major slumps in travel activities. In this phase, many workers were furloughed; some of them found work in other industries, which sometimes provided more-regular and family-friendly working hours as well as better remuneration. After things had returned to normal, many hospitality, food service and catering companies faced difficulties in regaining their old staff or recruiting new staff. Many vacancies could not be filled – a condition we can still observe in 2023.

The situation is totally different for importers, distributors, exporters and wine merchants: at 32% to 36%, respectively, they are comparatively less affected by the labor shortage. The reason? Because workers specifically skilled in wine tend to have more-regular working hours and are not subject to seasonal fluctuations, they often are permanently employed.

What kind of staff are wineries lacking?

Wineries mostly lack seasonal workers. Almost two out of three companies (63%) state that they lack temporary workers during the harvesting or the holiday seasons, which bring the greatest rush of tourists (Figure 2). Traditionally, they have been able to fall back on nonworking homemakers, retirees and students as a silent work reserve to be activated for the labor-intensive grape harvest season. However, the rising share of women in the labor market, a higher retirement age and greater financial security have dried up most of those reserves. Due to low birth rates in younger cohorts, there are also fewer and fewer students that could help out – and those who remain are strongly courted by other industries with sometimes high wages.

This is why in many Central European countries and regions – like Germany, Austria and Northern Italy – the lion’s share of seasonal workers over the last 30 years has hailed from Eastern Europe. Often, they established firm ties here over time, with seasonal workers’ entire families living and working at the same operation – an exceedingly efficient arrangement for wineries. A sharp rise in the minimum wage has made working in countries like Germany more attractive, but income opportunities have also become far more attractive in workers’ home countries. Add to this the fact that emerging countries in Eastern Europe are also facing severe staff shortages now due to dwindling birth rates.

Figure 2: What kind of staff is missing for wineries?

Countries such as Australia and New Zealand, where half of all companies can’t find sufficient seasonal workers, suffer mainly from the Covid-induced tourism slump. In addition, the pandemic also prevented the arrival of seasonal work-and-travel staff. The global recovery might improve the situation, but sharply increased airfares complicate the return of these migratory laborers. The shortage of seasonal workers is also severe among wine producers in Portugal (94%), Spain (77%) and California (73%). One out of two winery laments not being able to recruit sufficient staff for wine production and filling. For the most part, skilled workers in those areas require a qualified professional degree. Since craftspeople and skilled industrial workers are in short supply in most industries anyway, wineries frequently compete with much more solvent industries. Many companies talk about their hopeless searches for truck and forklift drivers. Three out of four co-ops are affected by the staff shortage in wine production. At 43%, this shortfall is not quite as pronounced at wine-growing estates because they can recruit family members to perform the work – especially at smaller operations. Shortages are especially pronounced in France, where 77% of wineries are looking for skilled staff for the cellar, followed by California, (67%) and Germany, Austria and Portugal (50%).

Every fifth producer seeks to fill vacancies in sales and distribution, gastronomy, and administration. The shortage of skilled and highly skilled labor is least severe in middle and senior management (only 4%), in part because of the small-scale nature of the wine industry, where leadership tasks in many firms are performed by family members. Only large enterprises have a need for employing executives – a need that’s set to grow in the future due to ongoing structural changes.

2. Staff Shortages and Their Effects

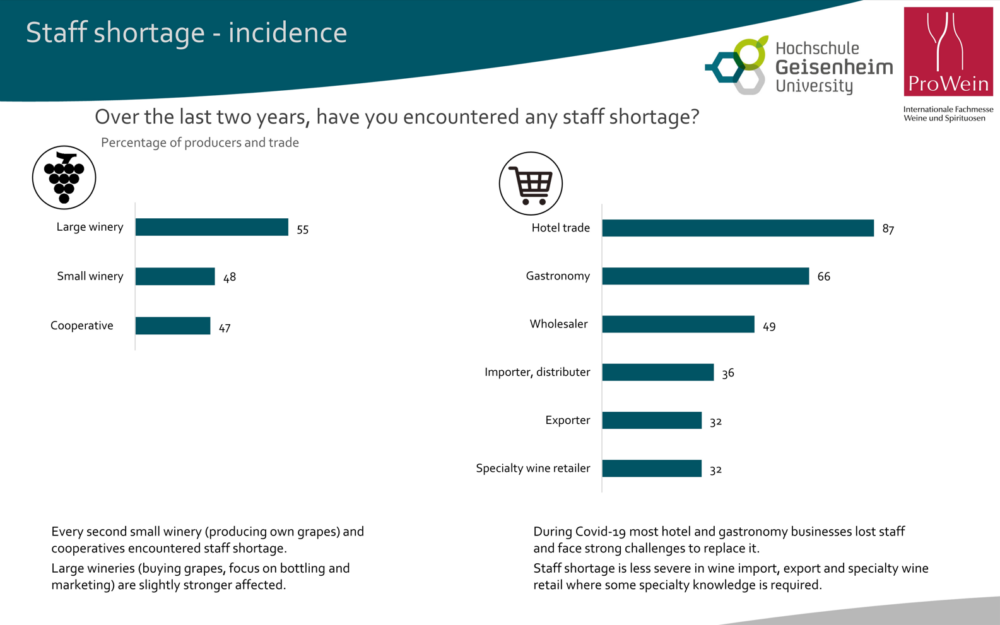

Predominantly, companies have compensated for staff shortages by instituting overtime and/or longer working hours (Figure 3). Above all, owner families and plant managers report a clearly increased workload: “I no longer have a day off.” “Family absorbs this through overtime, including on Sundays.” “As a family, we work around the clock.” “We have to work significantly more, leaving no time for family or breaks.” Numerous comments show that family-run businesses have already reached their limit, leaving them unable to compensate for any further aggravation of the situation. The additional economic worries here often lead to extremely high mental burdens, resulting in burnout. If family members then drop out, economic worries are aggravated even further by the markedly higher costs caused by external replacements. Finally, the socially and economically unsustainable labor requirements in wine-growing operations also reduce the chances of passing the winery on to the next generation, members of which often wonder whether this huge amount of work is really worthwhile.

Staff shortages also directly impact companies’ output. A third of all companies failed to deliver on their quality or service level goals. The harvest was delayed, resulting in a lower-quality grape harvest. Wine businesses were unable to provide gastronomy and hospitality customers the services they desired. In order to keep up existing processes, they had to partially reduce capacity. Some winery taverns, restaurants and hotels deliberately curtailed their offerings to ensure sufficient service levels for the remaining tables and rooms. Nearly one in four companies had to put up with sales losses caused by staff shortages because they could no longer offer all their products or services. Almost one in five companies (18%) reduced their service hours or could only deliver with delays (16%).

The Staff Shortage in the Wine Industry (JPG 3)

Already, staff shortages are impacting the industry’s long-term development. Some 36% of companies were unable to use new business opportunities or had to cut back on planned growth. One in four companies, especially wine estates (32%) and hotels (33%), had to outsource specific jobs to third-party service providers due to a lack of sufficient in-house staff. In part, the profit margin required by external service providers reduces the company’s profit.

3. How do Companies React to the Current Situation?

Companies reacted to staff shortage with a host of measures:

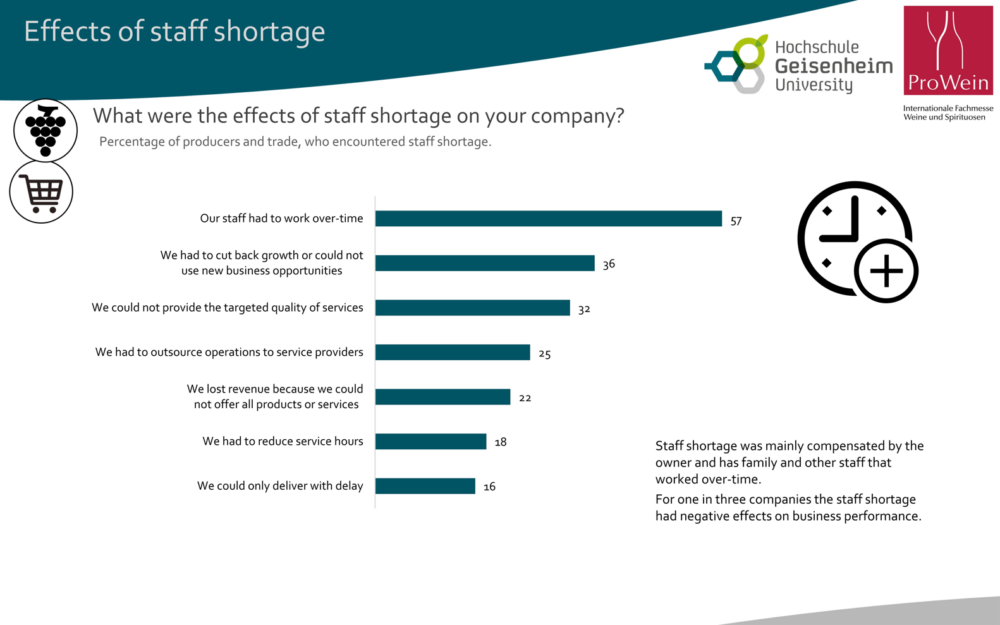

- Every other company markedly increased and widened the scope of its search activities (Figure 4).

- Every fourth company recruited staff with insufficient skills to then train them in-house – which, in turn, requires additional time.

- Every third company improved working conditions to retain existing staff – not an easy task considering that overtime work is often required at the same time. Companies also report team-building activities and measures.

- In view of staff shortages, every fourth company raised wages for both existing and new staff members. With this move, however, many companies are coming up against economic limits, putting additional pressure on the economic sustainability of many companies in the wine-growing sector, which was already weak before the crisis. The companies with the least room to maneuver in terms of profitability will face bigger difficulties in the war for suitable talent. Scarce labor resources tend to migrate to sectors with higher added value, higher wages and better working conditions. Some business owners say they intend to abandon their vineyards or businesses because they earn less for their working time than their staff. This means that rising wages also boost opportunity costs for owners.

Figure 4: Companies’ reaction to staff shortage

Because the demographics in many wine-growing countries will aggravate staff shortages even further in the future, it makes economic sense to automate seasonal work – thereby compensating for this shortage. Every fifth company has undertaken automation and digitalization measures. Above all, this benefits flat vineyards, where large-area mechanized pruning and harvesting makes sense, and the use of robotics seems possible. Steep vineyards not suitable for robotics will lose even more ground due to the higher costs associated with scarce labor and the effects of climate change.

4. What Does the Future Look Like? Opportunities and Risks

What are the threats and opportunities in view of the future availability of staff? Over 70% (Figure 5) feel that the higher salaries paid in other industries will entail further staff losses. Every other respondent also states the low profitability of the wine industry as a reason, because it limits the sector’s attractiveness. On the flip side, 51% of companies view proximity to nature and to the natural product that is wine as a chance to make this sector attractive for prospective future employees.

More than half (57%) of the companies polled expect automation and digitalization to rise further, all triggered by the labor shortage. Some, however, especially large enterprises and cooperatives, will be able to benefit from economies of scale – as they are in a position to bear the high required investment and maintenance costs. These processes also increase the economic pressure on viticulture operations.

Figure 5: Expectations for the future – threats and opportunities

Most companies (54%) are convinced that the industry will also depend on immigration and international seasonal workers in the future. However, whether levels seen in the past can be maintained going forward remains questionable due to changing circumstances.

In the eyes of many companies, the fascination of the product wine and working in nature are a special strength of this industry, making it particularly attractive for potential workers. In fact, the younger generation is strongly interested in “green” professions and sustainability issues. This industry can definitely score points in those areas.

Unlike during past economic crises, the number of available staff is not rising. As a result, only a very small number of enterprises considers the current economic crisis an opportunity for recruiting staff more easily. What’s more, many countries are affected by staff shortages across many industries, so plenty of firms shy away from firing employees.

5. Outlook

The wine industry is faced with the major challenge of recruiting and retaining staff. The sector will adapt and increasingly automate areas that are especially labor-intensive. This will drive structural change in the sector and lead to further consolidation in wine production. Wine trading, in contrast, will for the foreseeable future remain a people’s business where establishing personal contacts counts. Here, the industry needs to stand its ground in the competition for skilled labor by offering appropriate remuneration and good working conditions and by promoting wine’s fun factor.

Issued in January 2024, the upcoming ProWein Business Report will examine the magnitude of staff shortages and shed some light on the status quo.